THERE ARE LESSONS LEARNED That should not require repetition.

Once learned they should become part of our experience’s vocabulary. The idea

that we need to repeat errors ad

infinitum to integrate a given idea suggests that emotion rather than

reason will guide thought and the action that derives from thought. I have an

acquaintance that flies. He commented to me that the hardest thing for a

neophyte pilot to learn is to trust his or her instruments. We are creatures of

habit. We are creatures whose habits are defined by the emotional response to

the data provided by our senses. Instruments are robotic; that is to say that

they are data points, unencumbered by emotion, and, to the degree that they are

well maintained and calibrated, will report accurately. When sensory

information is unclear, the data provided by the instruments is not open to debate.

I think

that the same idea can be translated to navigation in a sailboat. I know that I

am a creature of habit. While I pride myself in being a rational person, the

truth is that I can find reason encumbered by emotions or misperception. My

greatest enemy is the false syllogism, one that proceeds from an erroneous

premise and is followed to an erroneous conclusion. I need to check myself

frequently. Healthy skepticism has always been my favored tonic to address risk

of falling prey to an inappropriate conclusion, and the necessary and logical

consequences of that choice.

There is a

misconception that navigation is plotting a course, riding the line, and

arriving in time for cocktails. GPS has done little to dispel this myth. Don’t

get me wrong, I am no Luddite: I love GPS, radar, and my chart plotter. But I

grew up with the art of coastal navigation known as “Dead Reckoning”. I learned

the arcane craft of deduced reckoning of a position, based on observations made

by the navigator compared with known information derived from the experience of

mariners and compiled in pilot books.

My charts

and pilot books were my grimoire, my parallel rules, my calipers, and hand

bearing compass were my magic wands. I could correct for magnetic deviation,

calculate and compensate for set and drift. Their meaning was shared like sacred gnosis to the

initiate. I could find the optimal course to steer and estimate time of

arrival; my prognostications became incantations, magic words spoken to guide

my craft over the face of the deep. To my mind, navigation is a communal act

that has specific and individual consequences. And I must confess that I became

an unfaithful practitioner of the ancient craft. I became lazy and trusted too

much in the line drawn on my chart plotter.

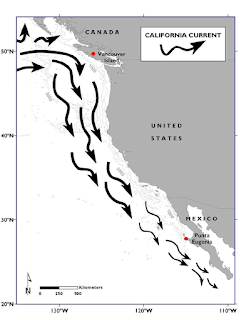

Anybody

that has sailed the coast of California knows that there is a current that will

have its way with you. It charges southward from Washington State, bringing

cold, artic water like a river, down the West Coast till it reaches Cabo San

Lucas. It can create fog and rain. It can create gales offshore. It is marked

by gyres along the way. It can carry you effortlessly in its caress to your

destination, or stop you in your tracks if you try to sail against it.

GPS is

blissfully unaware of the California Current.

And, in the

sophomoric certainty that partial knowledge can incite, I became the navi-guesser

rather than the keeper of knowledge and arbiter of the experience of preceding

generations of mariners. The line drawn on my chart plotter said that I would

arrive at the mouth of Channel Islands Harbor. The speed calculations provided

the time. But what of set and drift? The instruments reported the data. They

were saying, “Dude, you’re falling short and might make Point Mugu, not Channel

Islands Harbor...”

What had

happened? I had not taken the whole context into account as I plotted my course

from the Isthmus at Catalina to my home port. I did not account for the current

that would push my craft to the East. Nor did I consider the information that

was suggesting that I needed to alter my course. This is not the fault of the

instruments, it is almost in spite of them. I loved having radar while crossing

shipping lanes. I could see vessels well before they would become visible to my

eye. But I scanned the horizon for oncoming commercial traffic. Here is the

issue: I had attributed omniscience to the instruments.

Navigation

is an art. It is as much alchemy as it is a data-driven pursuit. The first

datum to consider is the limitation of the tools. I had not done that. This is

not the error of a Luddite, it is the error of a child of technology. I would

encourage all of us to embrace both the alchemy and the chemistry of

navigation. In that balance we find art. And as the poet has said: “Lessons learned are like bridges burned, We

only need to cross them but once…”

Fair winds

and following seas,

- Pablo.

Thanks

for spending a few moments with us. Please take a moment to join our mailing

list. Feel free to leave a comment or a question.

No comments:

Post a Comment